21 The shapes of time

For a museum, the goals are ambitious, both in terms of content and also values and ideals. The Museum of Tomorrow’s narrative seeks to present the infinite variety of the Universe, go through the bases of life and reveal the moment we are experiencing. Moreover, it intends to inspire reflection and call on people to construct a future based on our choices for the tomorrow we want. What physical space would be able to host a venture like this? And how could we ensure that a message of such complexity would be presented so as to enchant the public? To tackle this challenge, both the architecture and museology involved in the design avoided the usual, well-known trails, preferring to engage in innovative paths. By doing so, Rio’s new museum has added to a series of institutions that at the start of the 21st century have promoted across the world a veritable revolution in hitherto-predominant museum design conceptions. The Museum of Tomorrow is a privileged setting for those who want to experience this debate and stay abreast of the latest chapters in this scientific, educational and artistic adventure.

Directing innovative initiatives such as the Museum of the Portuguese Language, the Soccer Museum, the Palace of Frevo and the Rio Art Museum (MAR), the Roberto Marinho Foundation has built up precious experience by making room in the country for a line of museums that seek to establish their relationship with visitors on new terms. Focused on this goal, these projects have sought to harmonize the three pillars underlying the genesis of a museum: its architecture, curatorship and museology.

Rio city government’s invitation to the Roberto Marinho Foundation to occupy Praça Mauá’s pier site with the Museum of Tomorrow represented a distinctive challenge, because unlike with the Museum of the Portuguese Language or the Rio Art Museum (MAR), itself, it did not involve occupying or adapting an existing building, but instead to a certain extent it meant starting from scratch. And this first step was taken by Mayor Eduardo Paes, who suggested inviting the architect Santiago Calatrava to design the structure that would host the new museum.

The negotiations between the Roberto Marinho Foundation and the architect represented a first move to integrate the different aspects that would make up the new museum’s profile. Another important moment was the foundation’s invitation to New York-based Ralph Appelbaum Associates to produce the museum’s exhibition design. Its founder, responsible for seminal projects such as the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C. and the renovation of New York’s American Museum of Natural History, has over the last two decades promoted a profound transformation in the creation of museums and exhibition design, working on five continents, in countries as different as the United States and Nigeria, Norway and China. Determination to propose that visitors immerse themselves in a given theme, always supported by a narrative, is the common characteristic of all the projects of this award-winning firm, which had already worked with the Roberto Marinho Foundation on the Museum of the Portuguese Language. This same objective would also prevail at the Museum of Tomorrow: to evoke a basic idea through a story, told not just through language, but also sensory experiences to be felt by visitors.

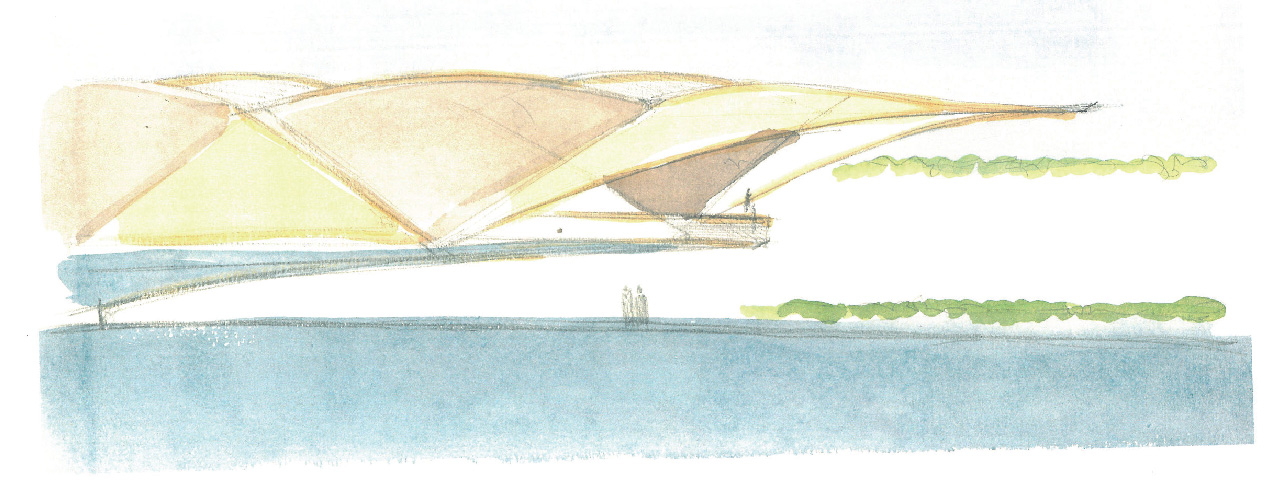

Santiago Calatrava, Santiago Calatrava, who was responsible for the architectural aspects of this triangular dialogue, which also involved content and museology, demonstrated sensitivity and respect for the landscape and history of the city when inserting his design in the port area. “When it became clear that we would be intervening in this area, the first thing to take into account was the existing buildings there”, said the architect, alluding to the nearby São Bento Monastery, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2014, and the building formerly occupied by the A Noite newspaper, in Praça Mauá: “We decided to establish a maximum height for the museum, of 15 meters, in order to avoid obstructing the view of these buildings from the sea.” The monastery’s position in the landscape led the architect to make a reference to Lisbon. “For me, it plays a role similar to that of the Jerônimos Monastery: it was an imposing image seen when arriving by sea. Our museum is low in order to allow this view”, he said. The building’s height also complies with a ruling by the National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage

Dialogue and harmony with the surrounding buildings – a concern of Calatrava’s – did not involve imitation, but contrast. This was the case, he says, in relation to the São Bento Monastery. During an interview, he removed one of his notebooks from his briefcase – he has thousands of such notebooks, all duly filed away by his wife in his office – and he began to sketch with a pencil. With agile movements, he outlined the silhouette of São Bento Hill, thick strokes suggesting a heavy, hulking mass. From the hill, the lines drawn by him raised up the straight and imposing shapes of the monastery.

The architect explained that, with the Museum of Tomorrow, he wanted to make a building “that is projected into the future.” Explaining his sketch of the monastery, he commented on the historic building’s link with the past: “If we stop to analyze things, we will surely see São Bento Monastery in this way: firstly, the hill, before it had any buildings, would be a great rock. Then the monastery building emerges from that rock, as if it were part of it. In addition, it is also built from stone. We could therefore think of it as belonging to a type of architecture, a mineral architecture.”

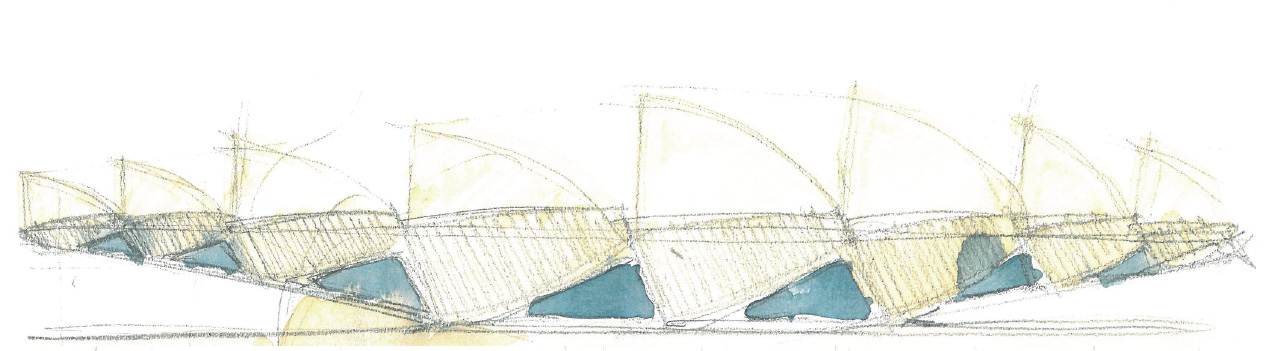

Consequently, he sees his design for the Museum of Tomorrow as a counterpoint to this characteristic. “Faced with this type of architecture, something leaving the rock, we decided to take a different approach, producing something so light that it looks like it intends to fly. If that architecture is mineral, ours is aerial.” Calatrava notes that the museum’s roof features a metal structure of a shape that resembles wings – and that these wings move in accordance with the sun’s position to capture solar energy.

This fact highlights another aspect of the contrast produced by him. “The first type of architecture – the monastery’s – is static and conveys an idea of permanence. Our design, with these mobile elements, seeks to convey the notion of something dynamic, changing, light. All this is important in understanding this contrast.” The sum of the qualities described by him practically amounts to a manifesto. “I believe that architecture from this point on will end up following this path, looking for a nature that is perhaps atmospheric, assuming the character of a living organism.”

According to Calatrava, the Museum of Tomorrow’s design represents a step forward in the evolution of his style. “In a way it reveals an effort to renew my vocabulary. Until then I had been working based on shapes associated with the human figure”, he explains, while tracing in his notepad the lines of a woman’s body.

We decided to take a different approach, producing something so light that it looks like it intends to fly.

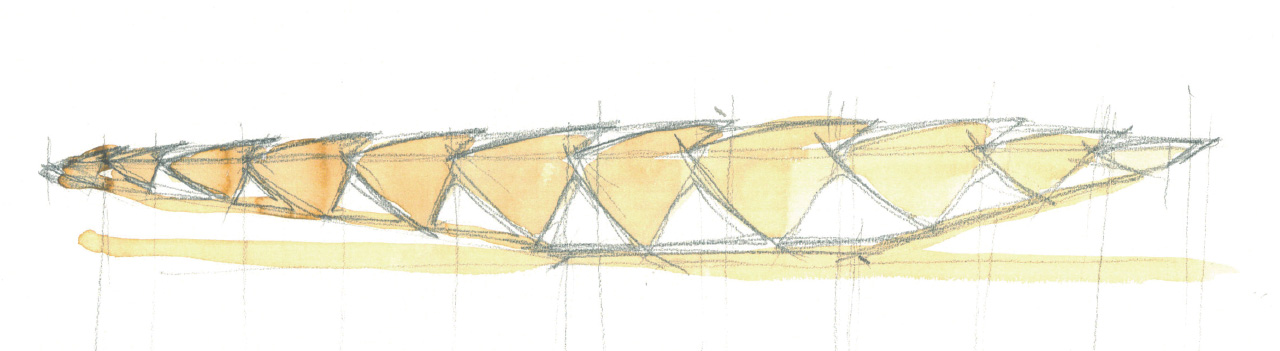

Known for painting dozens, sometimes hundreds, of watercolors before finding the solution to be applied to a new project, the architect saw the possibility of a different path during a visit to the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Garden before he started to design the Museum of Tomorrow, in 2010. Observing some flowers of the bromeliad family, typical of the Atlantic Forest, he became intrigued by the complexity of their shape. This was the first step that would lead him to change the model of the human body for that of a plant. Worked on in a new series of watercolors, his impressions were slowly digested and decanted until transforming into the seed of the Museum of Tomorrow’s design. “It influenced me”, says the architect. “This here is a clear reference to the world of plants, to organic growth. As with my sculptures, this design transmits a sense of growth. This series of elementary rhythms has something to do with plants.”

Calatrava is the first to admit that the impact, in plastic terms, exerted by his design is also sculptural. In Rio for a last visit to the Museum of Tomorrow’s construction site before its opening, the architect also expressed enthusiasm for that summer’s outdoor exhibition of seven enormous sculptures of his along Park Avenue, New York – large metal structures, some in bright colors. “I express myself more freely in sculptures because they are plastic creations. In architecture, the process is obviously much more challenging. It is a structure that needs to be functional as a museum.”

The experience accumulated by the architect in recent years, spanning a portfolio of major projects in countries such as Spain, Belgium, the United States and China, has confirmed his belief in architecture’s transformative powers in the cities where it is present. “Great public works are capable of changing cities, creating new spatial points of reference. However, this does not just mean creating iconic buildings”, he says.

This new way of conceiving of museums implies the creation of an environment in which numerous resources – from lighting to audiovisual media, from appeals to the senses to indoor architecture – are employed in order to make visitors experience a certain item of content or information.

The fact that museums have played a prominent role in these experiences is significant. Among the many high-impact designs signed by Calatrava are the Milwaukee Art Museum in the United States, and the City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia, Spain, completed in 2009. “It is necessary to understand that these projects should not be seen in isolation, but in the context of their cities. Museums in particular, which have experienced a revival for some years, are not only centers for spreading culture, but also play the role of urban myths – a bit like the great train stations in the European capitals in the 19th century – that are capable of transforming cities.”

According to Calatrava, the experience of Valencia – a project on which he worked for around 20 years – is especially illustrative of this point. “I believe we managed to achieve this objective with the Palace of the Arts in Valencia, located in what was one of the most neglected parts of the city, near the port, a post-industrial, obsolete and derelict area. The area has now turned into one of the city’s most visible places, where people most want to live. Not only was the urban landscape transformed, but a new benchmark for people and the city was also created. The city’s image among visitors and inhabitants themselves has changed a little.”

In the case of Rio, the most obvious sign of this transformation, however, is perhaps the disappearance of the “Perimetral” elevated highway from Rio’s landscape. “One of my greatest sources of satisfaction was the recognition of the former Perimetral as something obsolete. By removing it, we have managed to restore the relationship between two axes, Avenida Rio Branco and Praça Mauá, with its monument. A genuinely urban connection has been created”, he says, pointing to the double row of trees running alongside the museum.

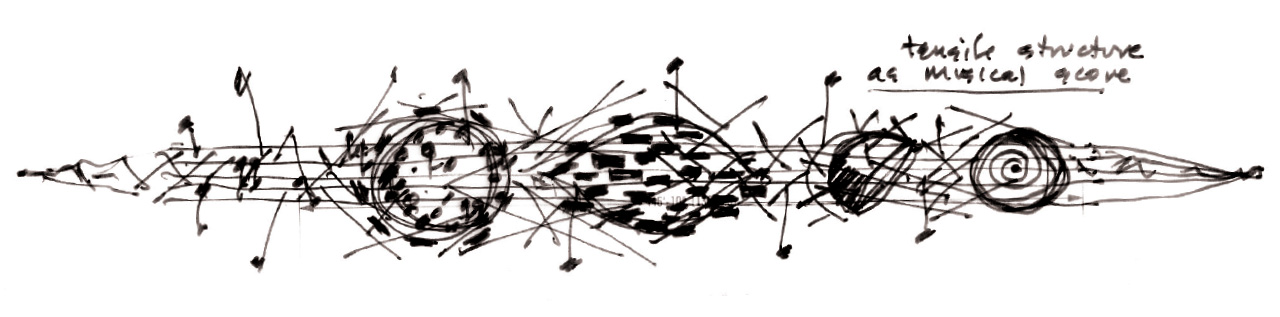

Elevated highways of this kind, a solution very much in vogue in the 1960s and 1970s, are not just a problem in Rio, he notes, mentioning one that dominates the landscape of Bronx, in New York. “There they produce a brutal impact on people arriving in the city. Here in Rio, this issue has been revolved with great elegance. I believe it is a pioneering scheme”, he praises, noting that the lack of anything, a free space, emptiness, also has meaning in an architectural design or urban plan. “As composers say, silence is also a part of music.”

The many technical resources required in the engineering plan were devoted to the construction work, which although complex, hosts a space that is in some way elementary: “The museum has a very archetypal plan. It is almost a cathedral’s nave, open on both sides. I use the image of a cathedral not so much for the atmosphere I wanted to create inside it, but for the nature of a certain type of building that can last 1,000 years, because it follows very elementary parameters, serving and adapting to multiple functions.”

The design and opening of the Museum of Tomorrow put Brazil in line with an emerging trend on the cultural stage across the world. Ralph Appelbaum is the leading spokesperson for the recent transformations international museums have been undergoing. Traditional museums used a formula familiar to many generations of visitors. Imposing staircases, classical columns and a central hall under a large dome received visitors in galleries that displayed collections of objects, generally protected in glass cases. “One wing or gallery did not always relate to the next one, and visitors were no more than observers in them”, says Appelbaum. He argues that “museums ought not to consider themselves as mere open portals, but should think of themselves based on their relationship with their visitors.” Inspired by this vision, he has become known for his efforts to bring to the fore in each museum a basic idea or narrative able to unify the set of experiences and content provided to the public.

In his opinion, this new way of conceiving of museums implies the creation of an environment in which numerous resources – from lighting to audiovisual media, from appeals to the senses to indoor architecture – are employed in order to make visitors experience a certain item of content or information. In them, the public are stimulated not only to think, but also to feel; to resort to both reason and emotion. The results have been encouraging, in a world where it is ever harder to draw rigid boundaries between entertainment and education. The “great ideas” destined to sustain these narratives also transcend the merely aesthetic or pedagogical level. According to Appelbaum, today’s museums “are essentially ethical constructions”.

Appelbaum came up with the idea of establishing a rhythm for the Museum of Tomorrow’s narrative, configured like a beating heart or musical score. This basic intention was maintained during the transformations through which the proposal went during the nearly five years of preparations. At the end of the process, there prevailed the museum design concept of occupying the building’s nave and unfolding through moments of the same narrative. “In this way we wanted to avoid the logic of a corridor, through which visitors merely advance through exhibition rooms, from one space to another”, explains project manager Deca Farroco.

It was up to creative director Andres Clerici – together with a team of curators and museum planners, as well as Vasco Caldeira, of museum exhibition design firm Artifício Arquitetura e Exposições – to tackle the challenge of clearly articulating the museum’s central idea and specifically applying these general principles to the content of each moment into which the narrative is divided. Clerici, who has experience in working with what he calls “museums of ideas”, explains that, at first, he plays a role similar to that of a psychologist, or even a medium, probing the team of curators and specialists in order to collectively discover the central idea that will guide the museum: “What is the narrative? What story do we want it to tell? We want to convey ideas through stories that engage the public in discussions about certain themes.” In the case of the Museum of Tomorrow, his narrative may be summed up in the belief that we have reached a unique and singular moment of human civilization. The Anthropocene is a condition created by us. Nothing will be able to remain as it was before, but the tomorrow to come is being created by us now.

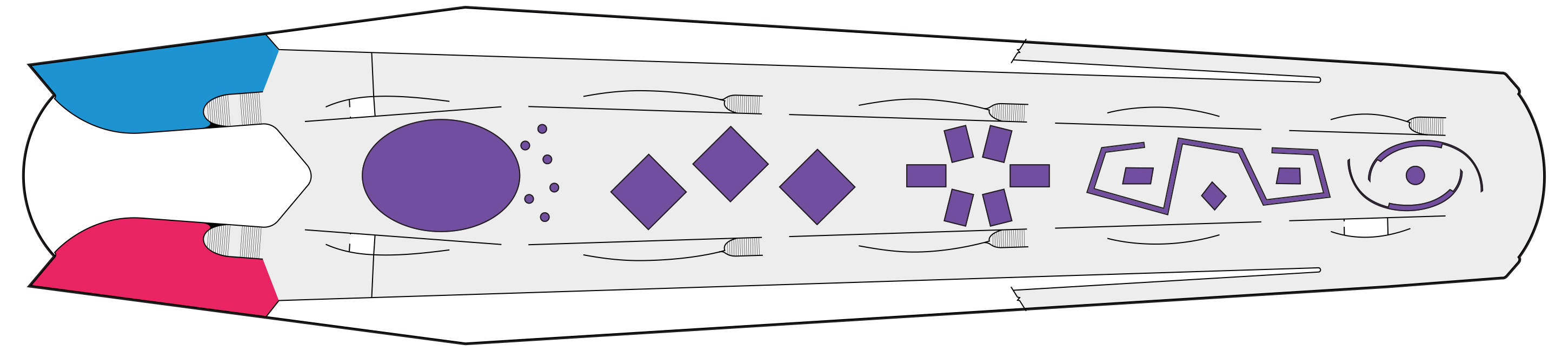

Once the narrative had been defined, it was only left to decide how to tell this story; to find a suitable way to transmit this content. The essential ideas should be conveyed mainly through experiences in a certain physical space, always in a way that engages visitors. In all, around 50 experiences are offered, all linked and distributed within five basic areas, embodying the great questions that humanity has always asked. Where did we come from? Who are we? Where are we? Where are we going? How do we want to proceed?; in other words, what life do we want to construct? The objective is for the public to experience and explore this sequence of questions, all related to different concepts and content, embodying certain elements of time.

In the view of Andres Clerici, the museum project’s biggest risk was falling into the trap of a “futuristic” vision. In the effort to transform content into experiences, the idea was to avoid a vision that, although created today, would look dated in a few years. In the pursuit of solutions that would resist the passage of time, the creative director favored “classic” forms that, due to their elementary nature, would not age.

For example, the first experience of the museum’s visitors is focused on the figure of a large black egg, representing the idea of origin and belonging to the Universe. It is a simple and timeless shape that will survive the passing of time well. Accordingly, squares, cubes and other elementary geometrical shapes that will always be recognized were used. In addition to the black egg, which symbolizes our origins, other examples of these shapes – simple and concise yet full of meaning – include three large cubes, each measuring 7 meters across. Called the “Boxes of Knowledge”, they feature information about the planet, life and culture. In the moment dedicated to Tomorrow, it was decided – after ruling out other possibilities, including a plaza – to choose an origami object, which presents content in other areas in an integrated way.

Also in relation to the world of shapes, the museum’s design has established a sensation of advancing from the solid and closed toward the open and abstract. “The egg present at the start of the visit is a solid shape, while the hut is open; it does not have a roof and it is not closed”, explains Clerici. Installed in the last moment of the narrative, the hut provides a space for people to think about their tomorrow. In doing so, the environment stimulates a new notion of belonging: no longer to a city or country, but to the Universe. The hut embodies a timeless form, like totems, which are also present in the exhibition. The important thing, according to the artistic director, is for visitors not to see all this from outside, as if they were watching a movie, but as a part of it. In this way, moments that are in some way theatrical are created.

Theater, involvement, experiences… A vocabulary that expresses the enormous array of resources available to the artists, theorists and technicians who are rethinking today’s museums. Avoiding the false dilemma that obliges people to choose between reason and feeling, reflection and emotion, both the exhibition design and architecture of the Museum of Tomorrow seem determined, in equal measure, to haunt us and make us think.

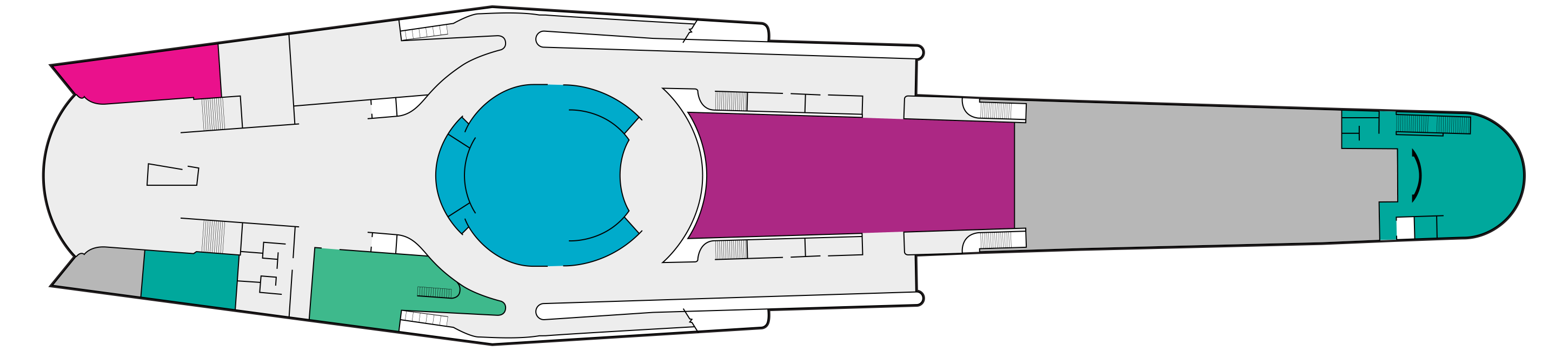

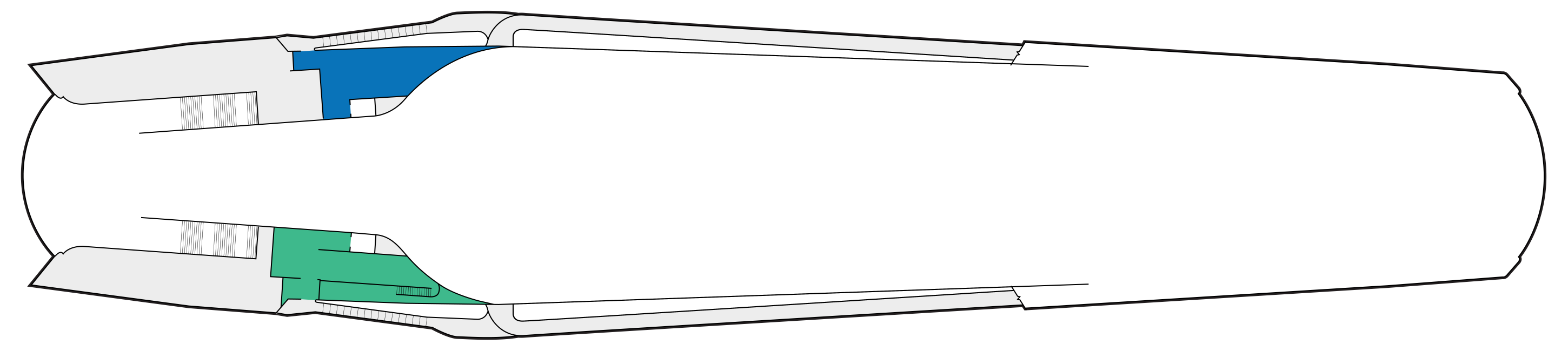

Loja

Loja

Store

Tienda

You are here

Usted está aqui

Information

Información

Tickets

Entradas

Checkroom

Guardarropas

Café

Café

Restroom

Baños

Elevator

Elevador

Elevator

Elevador

Auditorium

Auditorio

Restroom

Baños

Restroom

Baños

Temporary Exhibition

Exposición Temporaria

Administration

Administración

Restroom

Baños

Elevator

Elevador

Restaurant

Restaurante

Laboratory of Tomorrow’s Activities

Laboratorio de Actividades del Mañana

Observatory of Tomorrow

Observatorio del Mañana

Elevator

Elevador

Elevator

Elevador

Meeting Point

Puento de Encuentro

Educational Area

Área Educacional

Elevator

Elevador

Elevator

Elevador

Main Exhibition

Exposición Principal

Restroom

Baños

Restroom

Baños

Restroom

Baños

Restroom

Baños

Restroom

Baños

Restroom

Baños

Restroom

Baños

Elevator

Elevador